My reading of choice tends to be contemporary Philadelphia non-fiction — its true stories, histories and cultural anthropology.

My reading of choice tends to be contemporary Philadelphia non-fiction — its true stories, histories and cultural anthropology.

Across nearly all of this writing from the 20th and early 21st century is a very unexpected theme: someone growing up angry and put-on in some forgotten neighborhood and developing a very hateful relationship with their city.

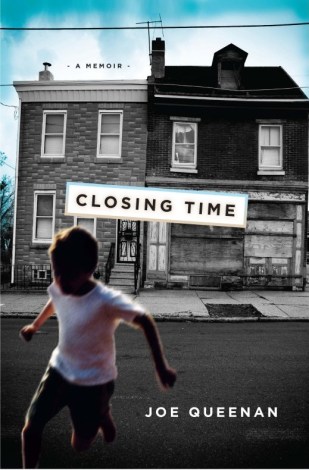

Joe Queenan, the Irish Catholic, self-styled Horatio Alger character of northwest neighborhood East Falls, writes the king of these stories, from what I’ve read, in his 2009 childhood biography called Closing Time. The son of an abusive drunk and a withdrawn mother. Queenan writes of chasing dreams that he felt he could never find in Philadelphia.

Find ‘Closing Time’ on Google Books. Buy the book at Amazon.

He was mostly angry. A lot of contemporary Philadelphia writing is. But Queenan has a quick pen — the likes of which has won him the praise of all the big writing critics we’re supposed to respect. Some of those passages kept me reading, in addition to his perspective (however bitter, though, I suppose, he softens in the closing chapters).

I wanted to share some that have the most relevance to those interested in urban development — and strong writing.

In looking back at his own childhood, he put out a great deal of perspective on the cyclical nature of poverty, something that reminded me of another book I read a couple years ago.

“[This salesman] was here to protect working-class people from their own worst instincts, to shield the proletariat from fads, whimsy, flights of fancy, lapses of sanity.” [page 125, hardcover]

And with poverty, also comes sentiment on violence:

“The mythology of urban survival asserts that boys from bad neighborhoods grow up to be tough, but in my experience, boys who grow up to be tough sooner or later get flattened by boys who grew up to be tougher or who have more tough boys in their entourage. The boys who survive growing up in rough neighborhoods are the ones who become cunning, who see trouble coming and either befriends its practitioners or get our of their way.” [page 132, hardcover]

With people with less education, often comes issues of race, something else he wrote vividly on:

When Irish Americans wanted to establish their bona fides in regard to blacks and Jews, they would say something like ‘I was standing on the corner in the rain, and this very nice Jewish girl came up and gave me her umbrella,” or “A very nice colored man gave me his seat on the bus.” These anecdotes were transmitted with a sense of befuddlement at the gallantry of the ethnic benefactors in question, leavened by a ham-fisted self-congratulation at being progressive enough to give credit where credit was due. Not all Jews were cheap, was the subtext of these testimonials, not all Negroes were ignorant and dangerous. Many were, but not all. The nicest thing you could say about Negroes in this environment was that were “refined,” unlike the cannibals who lived right next door to them.

“There was nothing especially mean-spirited about this way of talking: white people acted as if affectionate condescension was magnanimous, perhaps even gutsy. What I learned growing up was that blacks and Latins were to be feared, Jews distrusted, Italians avoided, and Poles ridiculed — but always on a case-by-case basis. Wasps we had no frame of reference for. All we knew about them was that given half a chance, they would row crew. [page 202, hardcover]

A throwback to his perspective on poverty:

“I already knew that poorly paid jobs merely led to other poorly paid jobs, and I had long since ceased believing in the secret wisdom of the proletariat.” [261]

And, hey, why not, from a Q&A he did with Philadelphia blog Phawker about the book, he riffs on this as well:

What is the biggest misconception that the non-poor have about poverty?

They think it’s just that you don’t have money. Being a little short on cash that week, that’s not being poor. This sort of recreational therapeutic poverty that rich kids go through when they go to Williamsburg, and they spend a year and a half living in some dirty apartment and they don’t have that much cash. Then they go to work for Morgan-Stanely. That is not what poverty is. Poverty is that feeling that no matter what you have, you should have bought the cheaper brand. It’s constantly thinking in terms of ‘I shouldn’t have gotten the Oreos, I should have gone with the Hydrox.’ You’ll always have crummy clothes, crummy appliances. You’ll buy things on time, and end up paying three times as much as they’re worth. You buy products that always break. It stays in your head, and it’s just very hard to dislodge. [Source]

Below, watch the satirist and author talk about how what we purchase can show glimmers of our class distinction:

Ultimately, the book’s sentiment — not only his own and not even necessarily untrue — and like most writers of his generation Philadelphia serves as a fine fill-in for his family and childhood, is summed up nicely in the end, a few pages from the the book’s close.

“[My father] loved Philadelphia, a city that is not especially easy to love.”

Did you or Queenan ever read James T. Farrell’s Studs Lonigan trilogy and that whole past century of angry Irish-American grow-up-in-the-city-crushed-by-alcohol-angry-dads-helpless-moms-greedy-employers-corrupt-politicians-clueless-church fiction, or are youse just re-inventing the wheel in a provincial-Philly-late-20th-Century vacuum after the main story’s moved on? Just curious. Love, Joe D.

This sounds like a terrific book I can relate to in more than a few ways – thanks for sharing Chris.

Joe D

I can admit I never read James T’s trilogy.

There are only a few stories out there and locality can at least something new…no? Maybe not.

Let me know if you get at it, Karl.

-cgw

I’m also interested in reading contemporary Philadelphia non-fiction. What other books do you recommend?

Yo Robert:

Read all of these?

http://christopherwink.com/2008/09/29/10-books-philadelphians-should-have-to-read-the-best-philly-books/

-cgw